Lately I’ve been noticing lots of things that seem to be true – and at the same time, completely counterintuitive.

Here are some examples:

- Being kind to yourself sometimes involves doing things you don’t want to do.

- When changing your behaviour, it helps to start by accepting yourself exactly as you are right now.

- In order to have a productive day, there are times when the best thing you can do in the moment is – absolutely nothing.

- If you want someone to listen to you, the most powerful thing you can do is listen to them.

- When you’re struggling to solve a problem, the solution often appears when you give up and pay attention to something else instead.

- Sometimes the best way to help another person is to stop trying to help them.

Having previously had a very rigid way of making sense of the world, I’ve found that the more my psychological health improves, the more I am able to tolerate paradoxes, both-this-and-that-ness, not-knowing.

Perhaps my new-found willingness to be in the presence of confusing and apparently contradictory ideas without demanding that one is right and the other wrong has come from learning about Dialectical Behavioural Therapy. DBT is an approach which can be helpful for people who find it difficult to regulate their emotions, thinking and behaviour (particularly those diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder, eating disorders or addictions, or at risk of suicide or self-harm).

The dialectic at the heart of DBT is this: we can accept ourselves exactly as we are right now, whilst also committing to doing things differently from this point onwards. It invites us to be gentle with ourselves for the things we are not able to control (for example, what happened to us when we were younger, how we behaved in the past when we didn’t know better) and to step up and take responsibility for improving things in the future (by learning to do things in new and healthier ways).

In life (as in DBT) it seems there is a constant balancing to be done, a strangeness to be embraced, a middle path to be found which is neither-this-nor-that.

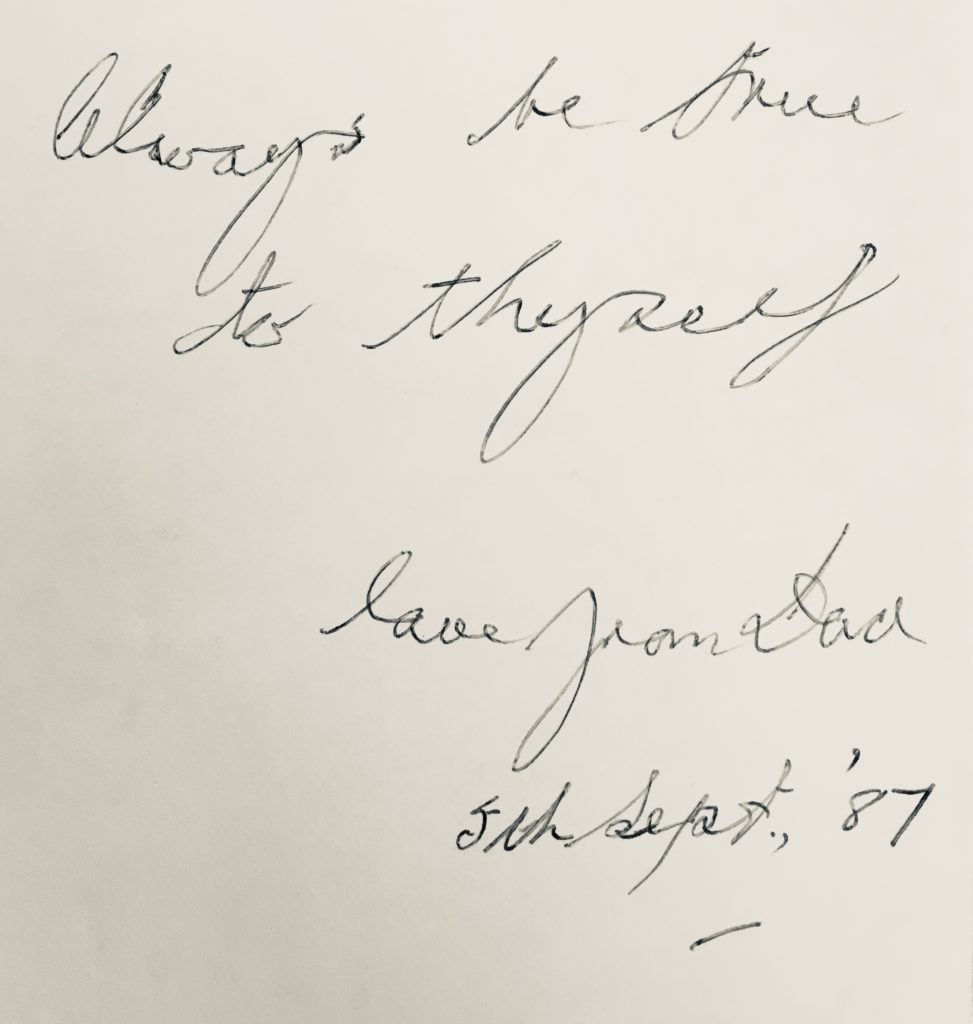

Increasingly, what I find to be wise and true cannot be expressed directly in language. It shows up in the spaces between words – an oddly beautiful, indescribable thing.